Elements of medieval horseriding

|

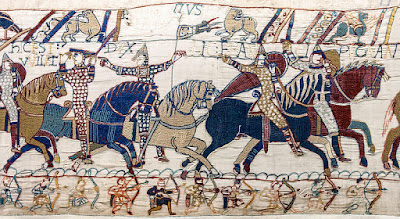

| Detail from the Bayeux tapestry, 11th century Public domain image |

I’ve already posted several articles on horses in medieval Europe. To go on with this series, here’s a very quick introduction to medieval horseriding.

There are, for the medieval period, no known treaties on horseriding, except the one written in the 15th century by Dom Duarte, (Livro da ensinança de bem cavalgar toda selaa) who was King of Portugal from 1433 to 1438. However, this text could be considered as belonging to the Renaissance, rather than to the Middle Ages. Yet the lack of written sources does not mean that there were no specific medieval riding techniques. These were taught and transmitted orally but part of them can be inferred from sources such as the iconography of the period.

A good example is the 11th century Bayeux tapestry (which shows the conquest of England by William of Normandy). Though the figures are simplified and the depiction cannot be considered as realistic, it gives a number of interesting clues on the way horses were ridden in Normandy at the time. Indeed, simplification does not mean that the representation of horses and riders is not based on reality, all the more so since there are some very lifelike effects in the wide range of movement attributed to them.

What can the tapestry tell us about horseriding in medieval Normandy? First, that the horses were very small (compared to modern standards) in proportion to their riders. Then, it gives information on the riders’ posture.

The Normans’ stirrups are worn very long, and their legs are held rather straight and a little bit forward. Their feet are well below their horse’s bellies. This type of riding can justify the use of very long spurs: the sometimes impressive size of the archaeological remains of spurs is explained by the need to reach the horse quickly and efficiently, which can be difficult given the position of the rider’s legs. The position of the legs seems to be reinforced by the shape of the saddle that helps maintain the rider in a very straight and stable position.

It can be noted that the position of the legs will vary according to the type of saddle used. In some parts of Europe, especially, in those where the influence of the Arabic culture was more important, the legs are bent, rather than straight and the rider does not sit in the same way.

To go back to the tapestry, some, but not all the riders wear spurs. Like the rest of the equipment, they are simplified but their presence could emphasise their importance. They were probably used to steer and control the horses, rather than push them forward, especially since the Normans do not seem to use their hands very much: the reins are loose and several of the riders are not holding them at all. This is logical: a knight has to have his hands free to hold a weapon and a shield.

Images are not the only sources that can give us information about medieval ways of riding. Some insights can be found in the literature of the time, such as chivalric novels. Complex riding techniques were certainly developed in the context of warfare: the destrier is not just a vehicle, used to go from one place to another but an essential ally and companion. The rider must be able to control him subtly and efficiently: developing a good riding technique (a good seat, the ability to communicate through natural and artificial aids with the horse, etc.) thus becomes a matter of life and death.

At the beginning of the Hundred Years war (1337-1445), Geoffroi de Charny wrote, in a treaty on the art of tournament, that a good rider must be able to be one with his horse, in order to resist blows from his enemies without falling off. He also adds that the horse must be well trained, since a bad horse will disadvantage a good knight.

On the other hand, Perceval, the Story of the Grail written by Chrétien de Troyes in the 12th century underlines that a perfectly trained warhorse is of no use to someone who has not been taught to ride such a steed. At the beginning of the story, the young hero is taught how to be a knight by a man he meets on his journey to the court of King Arthur. This passage is interesting for it gives a little (too little) information on medieval horseriding and highlights the fact that the mastery of a good riding technique was an essential condition to become a good knight. The correct use of spurs seems to have been an import element of this technique. Frustratingly, the author does not go into much detail, probably because the intended public (an aristocratic one) of the story knew all about it already. Good horsemanship was a quality every knight had to acquire.

An extensive study of the tack used on medieval horses could probably give more clues, as well as the confrontation of the different sources available with later treaties. What has to be highlighted is that the absence of written treaties does not equate with the absence of riding techniques. And that hasty conclusions must not be drawn from what sources we have (such as the impressive spurs that led many people, including historians, to state that medieval horseriding was barbaric).

Comments

Post a Comment