The portrayal of mares in medieval Europe

|

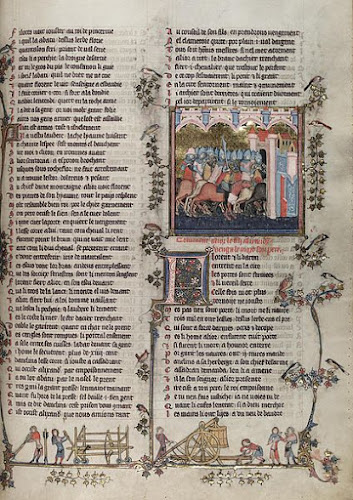

| Old French manuscript Roman d'Alexandre, completed in 1344 in Tournai. Fol. 201r. Image from Wikimedia commons |

In medieval Europe, horses were highly anthropomorphised. Among other things, correspondences were made between the sex of a horse and that of his/her rider. Warhorses were stallions and associated with virility. As for mares, they represented feminity and were sometimes assimilated to women – and not always in a positive manner!

Though the virile warhorse was granted human qualities such as courage and loyalty, the way mares were anthropomorphised could reflect the wariness and even suspicion some authors, especially ecclesiastical ones, harboured towards women. For instance, mares were described as full of lust and vanity, with links to witchcraft.

Here is what Brunetto Latini (1220-1294) says about them:

“Their lust can be extinguished if their mane is cut. (…) From them comes a love spell that is found on the brow of their foal; but the mother takes it away with her teeth, because she does not want this thing to come into the hand of man. However, if you take this thing away, you must know that the mother will no longer give milk to her foal.”[1]

A similar passage is found in Barthelemus Anglicus’s encyclopedia, written in 1247. The author quotes Pliny as a source for this information:

“He says that there is, on the foal’s brow, a small black pellet, the size of a dried fig, that the mother licks with her tongue and cuts with her teeth and hides it; and she will not give it milk until this skin is cut. And this skin is called by Pliny a love spell, because it is used by witches when they want to make a person suffer because of love.” [2]

Barthelemus Anglicus also mentions the mares’ lust and vanity: “the mare is proud of her mane and angry when it is cut, and her lust is extinguished when her mane is cut (…).” However, he also describes the love they have for their foal:

“If one dies leaving her foal behind, another will feed him like her own. A mare gives birth in summer and loves her foal more than any other beast. And she loves her foals and when she loses one, she will feed another one and will love it like her own.”

As you can see, this author’s description of the mare hesitates between that of a lustful female and that of an ideal mother. Her portrayal is as ambiguous as the perception of women was at the time. At any rate, the feelings attributed to the mare are humanised. The mare’s capacity to love her foal, described as unique in the animal kingdom, makes her, in this aspect, the ideal counterpart of the valiant, male destrier who, you may remember from previous posts, was described by those authors as the most intelligent and loyal of all beasts.

Those portrayals are found in encyclopaedias, in “scientific” texts. But do mares appear, like destriers, in chivalric novels? In those books, male horses are numerous. If you take the 1170 Romance of Alexander (based on the legend of real life Alexander the Great, with many fantastical adventures) by Alexandre Paris,[3] for instance, you will find that the descriptions of battles especially, are rhythmed by the names and characteristics of destriers. To quote a few: “Valerion, a chestnut destrier from Spain,” “Ferrant [typical name for a grey horse] of Navaille,” “a black horse called Pierne,” “The horse Joab [who was] treacherous and deceitful.” All those horses are individualised by their name, colour and sometimes character. And they are all male: not surprising, since knights only ever rode stallions in battle.

However, a mare does make an appearance during one of Alexander’s adventure. The hero finds himself riding one as he disguises himself to play a trick on one of his enemies, the king Porrus. Here’s an approximate translation of the passage:

“Alexander is riding, he wants to go to the market on a mare no one ever saw the like of. She was neither black nor white: you could not decide what colour that beast was, and never knew how to amble. When the king was on her back and he wanted to turn, she did not go forward before she started to go back. The king stroke her with his spurs (…) and she started to buck very strongly, and to jump on the side and to throw her feet. “Why, said Alexander, cannot she see clearly?” “She can, said his men, but she wants to play.””

This mare is the opposite of the destriers of chivalric novels: she is female, she has no name and no colour. She cannot amble, so that means she is neither a valuable palfrey, nor actually a very well trained horse, as is also shown by her reaction to the spurs.

Her quirks mean that she has more personality than most of the other destriers (apart from Bucephalus, Alexander’s horse). Interestingly, Alexander assumes that her misbehaviour is due by a physiological issue but his men explain that she was just playful, recognising her individuality and personality. She is portrayed as being quite independent, refusing to submit to man.

However, this may not really be seen as a positive trait: everything in her portrayal shows that she is not a fit mount for a king, because of her sex and because of her behaviour. Yet, due to what is happening in the story at that moment, she also becomes a reflection of her rider: he wants to play a trick on one of his enemies by disguising himself, so it is logical that he should be riding a playful horse who, like him, is up to no good.

Like the mares in the encyclopaedias, this one is at the centre of a rather ambiguous portrayal, half positive (she has individuality and is chosen by Alexander to be her accomplice), half negative (for the same reasons, actually) and determined by anthropomorphism.

But isn’t that anthropomorphism still at play nowadays when mares get a bad press for being moody and temperamental? Aren’t the clichés we still have about them inherited from older times?

[1] Brunetti Latini, Li Livres dou tresor, ed. P. Chabaille, Paris 1863

[2] Jean Corbechon, Livre des propriétés des choses, ed. B. Prévot, in B. Prévot, Orléans – Caen, 1994

[3] Alexandre de Paris, Le Roman d’Alexandre, ed. E.C. Amstrong, Paris 1994

Comments

Post a Comment