Backing my 5yo pony using medieval techniques as an inspiration

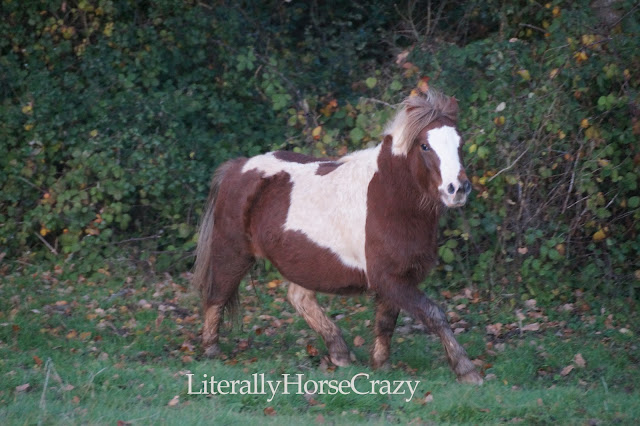

Having been given two Dartmoor Hill ponies at the beginning of my PhD research on the breaking-in of medieval horses, I was able to try out some techniques found in a training method written by the 13th century Italian knight Jordanus Rufus. The ponies were 18 months old when I got them and, being Shetland crosses (probably, who knows with Dartmoor Hillies) tiny. Riding them was, at first, out of the question. However, as the months, then years passed, while Topaze, the mare remained tiny, Diamant, the gelding had a growth spurt. I started to think about backing him, not for me to ride him on a regular basis, but to give him additional skills and to keep him occupied: whereasTopaze shows little interest in human interaction, Diamant is always trying to get people's attention or to go out of the field. So I thought, why not back him and then find him a little rider who would take him on hacks.

I used a tape measure to get an idea of his weight last Autumn. He was a whooping 270 kg. Since my own weight is less than 25% of that, I decided that he should be fine, as long as the rides were kept short. I was quite excited by the idea of backing him: it would be my first time doing something like that. I also thought it would be a good opportunity to go on doing what I was attempting when I first started working with those ponies: trying out medieval techniques.

When Jordanus Rufus explains how the horse must be ridden for the first time, he says that it must be done after a period of groundwork, to get the horse accustomed to the bit. Then, the rider must get on, as calmly as possible, without any saddle and without wearing his spurs (this last comment was important in a medieval chivalric context, where spurs were not only an important piece of riding equipment but also a symbol of status). The bareback riding then had to be done every day, for a month, at a walk, in the company of a person on foot if necessary.

This is an interesting method, since today, the saddle is often introduced before the rider. Given that medieval saddles did not necessarily fit horses very well (Rufus himself devotes a chapter of his veterinary treatise to the injuries caused by saddles) and that saddle pads were not necessarily used, a bareback rider might have been more comfortable for the horse. Moreover, it means that there is no girth giving the horse weird sensations on his belly and no stirrups flapping around. In some ways, it can also be safer for the rider, with no risk of feet getting stuck in stirrups in the event of a fall. I personnally think that the bareback riding might also have been done for symbolical reasons: Rufus's training insists a lot on the bond between human and horse. There is also the idea, in parts of medieval literature, that knight and destrier have to become one. What better way to become one than to ride bareback? It definitely helps to feel the horse better and become more aware of his reactions.

Rufus's backing of the horse takes place when the latter is either two or three years old. Because of the modern knowledge we have about the growth of the horse, and because of Diamant's small size, I waited until he was five to do anything. That gave me the opportunity to do plenty of groundwork and build our relationship on the ground. Rufus also uses a bit, which I decided not to do. For many reasons, I prefer to ride bitless and believe it is just as safe as the alternative if the proper training has been done.

For my first ride on Diamant, I got on bareback. It went, in my opinion, really well. I had previously practiced leaning on him, putting increasing weight on his back. When I got on "for real", he remained very calm. I had been preparing myself to some level of agitation, but no. He took it all in his stride. It demonstrated to me how all the preparation that went on beforehand had been important. I let him take a few steps. He didn't seem bothered at all by me being on his back and responded well to attempts at stopping him, using the reins, my legs, and vocal cues.

The next session, a few days later, I still worked on stopping, letting him walk when he wanted then asking him to stop. The session after that, I taught him how to go forward on cue, slightly pressing my legs and clicking my tongue. Then we started to add direction.

It was all going very well and Diamant was making massive progress. Unfortunately, a couple of incidents happened in the school on two occasions, scaring him. I even fell off when he got frightened the second time and bolted. He did come back to check on me as I lay on the ground, which I appreciated. I got back on him to end the session on a better note but he was definitely nervous and agitated. I decided to pause the sessions for the time being and build back confidence on the ground. It was a bit of a disappointment to have those backwards steps, but I had been expecting something like that to happen.

I was also a bit comforted by the fact that one of the manuscripts containing Rufus's training method makes an addition, saying that if the rider falls off, he should ask someone else for help. This is a very interesting addition since in most of the other versions of the text, there is no reference to anything going wrong during the breaking-in. This makes it a more realistic interpretation of the training, demonstrating the awareness that despite the medieval idealisation of the rider's skills and of his bond with the horse, things can be complex in real life.

Once the weather has settled, and Diamant has regained his confidence, I will hop back on and go on with the training. And I might still make a tiny warhorse out of him!

Comments

Post a Comment